Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

| Orbital mechanics |

|

Equations

|

|

Efficiency measures

|

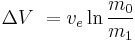

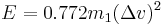

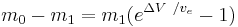

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, or ideal rocket equation is an equation that is useful for considering vehicles that follow the basic principle of a rocket: where a device that can apply acceleration to itself (a thrust) by expelling part of its mass with high speed and moving due to the conservation of momentum. Specifically, it is a mathematical equation that relates the delta-v (the maximum change of speed of the rocket if no other external forces act) with the effective exhaust velocity and the initial and final mass of a rocket (or other reaction engine.)

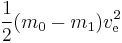

For any such maneuver (or journey involving a number of such maneuvers):

where:

is the initial total mass, including propellant,

is the initial total mass, including propellant, is the final total mass,

is the final total mass, is the effective exhaust velocity (

is the effective exhaust velocity ( where

where  is the specific impulse expressed as a time period),

is the specific impulse expressed as a time period), is delta-v - the maximum change of speed of the vehicle (with no external forces acting).

is delta-v - the maximum change of speed of the vehicle (with no external forces acting).

Units used for mass or velocity do not matter as long as they are consistent.

The equation is named after Konstantin Tsiolkovsky who independently derived it and published it in his 1903 work.[1]

Contents |

History

This equation was independently derived by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky towards the end of the 19th century and is widely known under this name and ideal rocket equation. However a recently discovered pamphlet "A Treatise on the Motion of Rockets" by William Moore[2] shows that the earliest known derivation of this kind of equation was in fact at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in England in 1813,[3] and was used for weapons research.

Stages

In the case of sequentially thrusting rocket stages, the equation applies for each stage, where for each stage the initial mass in the equation is the total mass of the rocket after discarding the previous stage, and the final mass in the equation is the total mass of the rocket just before discarding the stage concerned. For each stage the specific impulse may be different.

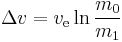

For example, if 80% of the mass of a rocket is the fuel of the first stage, and 10% is the dry mass of the first stage, and 10% is the remaining rocket, then

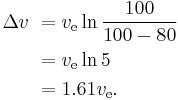

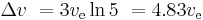

With three similar, subsequently smaller stages with the same  for each stage, we have

for each stage, we have

and the payload is 10%*10%*10% = 0.1% of the initial mass.

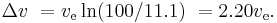

A comparable SSTO rocket, also with a 0.1% payload, could have a mass of 11% for fuel tanks and engines, and 88.9% for fuel. This would give

If the motor of a new stage is ignited before the previous stage has been discarded and the simultaneously working motors have a different specific impulse (as is often the case with solid rocket boosters and a liquid-fuel stage), the situation is more complicated.

Energy

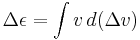

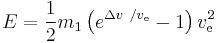

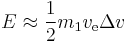

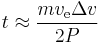

In the ideal case  is useful payload and

is useful payload and  is reaction mass (this corresponds to empty tanks having no mass, etc.). The energy required can simply be computed as

is reaction mass (this corresponds to empty tanks having no mass, etc.). The energy required can simply be computed as

This corresponds to the kinetic energy the expelled reaction mass would have at a speed equal to the exhaust speed. If the reaction mass had to be accelerated from zero speed to the exhaust speed, all energy produced would go into the reaction mass and nothing would be left for kinetic energy gain by the rocket and payload. However, if the rocket already moves and accelerates (the reaction mass is expelled in the direction opposite to the direction in which the rocket moves) less kinetic energy is added to the reaction mass. To see this, if, for example,  =10 km/s and the speed of the rocket is 3 km/s, then the speed of a small amount of expended reaction mass changes from 3 km/s forwards to 7 km/s rearwards. Thus, while the energy required is 50 MJ per kg reaction mass, only 20 MJ is used for the increase in speed of the reaction mass. The remaining 30 MJ is the increase of the kinetic energy of the rocket and payload.

=10 km/s and the speed of the rocket is 3 km/s, then the speed of a small amount of expended reaction mass changes from 3 km/s forwards to 7 km/s rearwards. Thus, while the energy required is 50 MJ per kg reaction mass, only 20 MJ is used for the increase in speed of the reaction mass. The remaining 30 MJ is the increase of the kinetic energy of the rocket and payload.

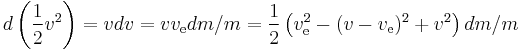

In general:

Thus the specific energy gain of the rocket in any small time interval is the energy gain of the rocket including the remaining fuel, divided by its mass, where the energy gain is equal to the energy produced by the fuel minus the energy gain of the reaction mass. The larger the speed of the rocket, the smaller the energy gain of the reaction mass; if the rocket speed is more than half of the exhaust speed the reaction mass even loses energy on being expelled, to the benefit of the energy gain of the rocket; the larger the speed of the rocket, the larger the energy loss of the reaction mass.

We have

where  is the specific energy of the rocket (potential plus kinetic energy) and

is the specific energy of the rocket (potential plus kinetic energy) and  is a separate variable, not just the change in

is a separate variable, not just the change in  . In the case of using the rocket for deceleration, i.e. expelling reaction mass in the direction of the velocity,

. In the case of using the rocket for deceleration, i.e. expelling reaction mass in the direction of the velocity,  should be taken negative.

should be taken negative.

The formula is for the ideal case again, with no energy lost on heat, etc. The latter causes a reduction of thrust, so it is a disadvantage even when the objective is to lose energy (deceleration).

If the energy is produced by the mass itself, as in a chemical rocket, the fuel value has to be  , where for the fuel value also the mass of the oxidizer has to be taken into account. A typical value is

, where for the fuel value also the mass of the oxidizer has to be taken into account. A typical value is  = 4.5 km/s, corresponding to a fuel value of 10.1 MJ/kg. The actual fuel value is higher, but much of the energy is lost as waste heat in the exhaust that the nozzle was unable to extract.

= 4.5 km/s, corresponding to a fuel value of 10.1 MJ/kg. The actual fuel value is higher, but much of the energy is lost as waste heat in the exhaust that the nozzle was unable to extract.

The required energy  is

is

Conclusions:

- for

we have

we have

- for a given

, the minimum energy is needed if

, the minimum energy is needed if  , requiring an energy of

, requiring an energy of

.

.- Starting from zero speed this is 54.4 % more than just the kinetic energy of the payload. In this optimal case the initial mass is 4.92 times the final mass.

These results apply for a fixed exhaust speed.

Due to the Oberth effect, and starting from a nonzero speed the required potential energy needed from the propellant may be less than the increase in energy in the vehicle and payload. This can be the case when the reaction mass has a lower speed after being expelled than before- rockets are able to liberate some or all of the initial kinetic energy of the propellant.

Also, for a given objective such as moving from one orbit to another, the required  may depend greatly on the rate at which the engine can produce

may depend greatly on the rate at which the engine can produce  and maneuvers may even be impossible if that rate is too low. For example, a launch to LEO normally requires a

and maneuvers may even be impossible if that rate is too low. For example, a launch to LEO normally requires a  of ca. 9.5 km/s (mostly for the speed to be acquired), but if the engine could produce

of ca. 9.5 km/s (mostly for the speed to be acquired), but if the engine could produce  at a rate of only slightly more than g, it would be a slow launch requiring altogether a very large

at a rate of only slightly more than g, it would be a slow launch requiring altogether a very large  (think of hovering without making any progress in speed or altitude, it would cost a

(think of hovering without making any progress in speed or altitude, it would cost a  of 9.8 m/s each second). If the possible rate is only

of 9.8 m/s each second). If the possible rate is only  or less, the maneuver can not be carried out at all with this engine.

or less, the maneuver can not be carried out at all with this engine.

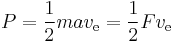

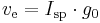

The power is given by

where  is the thrust and

is the thrust and  the acceleration due to it. Thus the theoretically possible thrust per unit power is 2 divided by the specific impulse in m/s. The thrust efficiency is the actual thrust as percentage of this.

the acceleration due to it. Thus the theoretically possible thrust per unit power is 2 divided by the specific impulse in m/s. The thrust efficiency is the actual thrust as percentage of this.

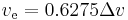

If e.g. solar power is used this restricts  ; in the case of a large

; in the case of a large  the possible acceleration is inversely proportional to it, hence the time to reach a required delta-v is proportional to

the possible acceleration is inversely proportional to it, hence the time to reach a required delta-v is proportional to  ; with 100% efficiency:

; with 100% efficiency:

- for

we have

we have

Examples:

- power 1000 W, mass 100 kg,

= 5 km/s,

= 5 km/s,  = 16 km/s, takes 1.5 months.

= 16 km/s, takes 1.5 months. - power 1000 W, mass 100 kg,

= 5 km/s,

= 5 km/s,  = 50 km/s, takes 5 months.

= 50 km/s, takes 5 months.

Thus  should not be too large.

should not be too large.

Derivation

Consider the following system:

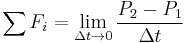

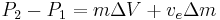

In the following derivation, "the rocket" is taken to mean "the rocket and all of its unburned propellant". Newton's second law of motion relates external forces ( ) to the change in linear momentum of the system as follows:

) to the change in linear momentum of the system as follows:

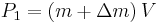

where  is the momentum of the rocket at time t=0:

is the momentum of the rocket at time t=0:

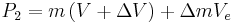

and  is the momentum of the rocket and exhausted mass at time

is the momentum of the rocket and exhausted mass at time  :

:

and where, with respect to the observer:

-

is the velocity of the rocket at time t=0

is the velocity of the rocket at time t=0 is the velocity of the rocket at time

is the velocity of the rocket at time

is the velocity of the mass added to the exhaust (and lost by the rocket) during time

is the velocity of the mass added to the exhaust (and lost by the rocket) during time

is the mass of the rocket at time t=0

is the mass of the rocket at time t=0 is the mass of the rocket at time

is the mass of the rocket at time

The velocity of the exhaust  in the observer frame is related to the velocity of the exhaust in the rocket frame

in the observer frame is related to the velocity of the exhaust in the rocket frame  by

by

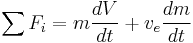

Solving yields:

and

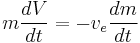

If there are no external forces then  and

and

Assuming  is constant, this may be integrated to yield:

is constant, this may be integrated to yield:

or equivalently

or

or  or

or

where  is the initial total mass including propellant,

is the initial total mass including propellant,  the final total mass, and

the final total mass, and  the velocity of the rocket exhaust with respect to the rocket (the specific impulse, or, if measured in time, that multiplied by gravity-on-Earth acceleration). The value

the velocity of the rocket exhaust with respect to the rocket (the specific impulse, or, if measured in time, that multiplied by gravity-on-Earth acceleration). The value  is the total mass of propellant expended.

is the total mass of propellant expended.

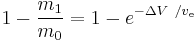

is the mass fraction (the part of the initial total mass that is spent as reaction mass).

is the mass fraction (the part of the initial total mass that is spent as reaction mass).

(delta v) is the integration over time of the magnitude of the acceleration produced by using the rocket engine (what would be the actual acceleration if external forces were absent). In free space, for the case of acceleration in the direction of the velocity, this is the increase of the speed. In the case of an acceleration in opposite direction (deceleration) it is the decrease of the speed.

(delta v) is the integration over time of the magnitude of the acceleration produced by using the rocket engine (what would be the actual acceleration if external forces were absent). In free space, for the case of acceleration in the direction of the velocity, this is the increase of the speed. In the case of an acceleration in opposite direction (deceleration) it is the decrease of the speed.

Of course gravity and drag also accelerate the vehicle, and they can add or subtract to the change in velocity experienced by the vehicle. Hence delta-v is not usually the actual change in speed or velocity of the vehicle.

Although an extreme simplification, the rocket equation captures the essentials of rocket flight physics in a single short equation. It also happens that delta-v is one of the most important quantities in orbital mechanics, that quantifies how difficult it is to perform a given orbital maneuver.

Clearly, to achieve a large delta-v, either  must be huge (growing exponentially as delta-v rises), or

must be huge (growing exponentially as delta-v rises), or  must be tiny, or

must be tiny, or  must be very high, or some combination of all of these.

must be very high, or some combination of all of these.

In practice, this has been achieved by using very large rockets (increasing  ), with multiple stages (decreasing

), with multiple stages (decreasing  ), and rockets with very high exhaust velocities. The Saturn V rockets used in the Apollo space program and the ion thrusters used in long-distance unmanned probes are good examples of this.

), and rockets with very high exhaust velocities. The Saturn V rockets used in the Apollo space program and the ion thrusters used in long-distance unmanned probes are good examples of this.

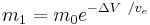

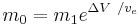

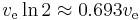

The rocket equation shows a kind of "exponential decay" of mass  , not as a function of time, but as a function of delta-v produced. The delta-v that is the corresponding "half-life" is

, not as a function of time, but as a function of delta-v produced. The delta-v that is the corresponding "half-life" is

Examples

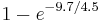

Assume an exhaust velocity of 4.5 km/s and a  of 9.7 km/s (Earth to LEO).

of 9.7 km/s (Earth to LEO).

- Single stage to orbit rocket:

= 0.884, therefore 88.4 % of the initial total mass has to be propellant. The remaining 11.6 % is for the engines, the tank, and the payload. In the case of a space shuttle, it would also include the orbiter.

= 0.884, therefore 88.4 % of the initial total mass has to be propellant. The remaining 11.6 % is for the engines, the tank, and the payload. In the case of a space shuttle, it would also include the orbiter.

- Two stage to orbit: suppose that the first stage should provide a

of 5.0 km/s;

of 5.0 km/s;  = 0.671, therefore 67.1% of the initial total mass has to be propellant to the first stage. The remaining mass is 32.9 %. After disposing of the first stage, a mass remains equal to this 32.9 %, minus the mass of the tank and engines of the first stage. Assume that this is 8 % of the initial total mass, then 24.9 % remains. The second stage should provide a

= 0.671, therefore 67.1% of the initial total mass has to be propellant to the first stage. The remaining mass is 32.9 %. After disposing of the first stage, a mass remains equal to this 32.9 %, minus the mass of the tank and engines of the first stage. Assume that this is 8 % of the initial total mass, then 24.9 % remains. The second stage should provide a  of 4.7 km/s;

of 4.7 km/s;  = 0.648, therefore 64.8% of the remaining mass has to be propellant, which is 16.2 %, and 8.7 % remains for the tank and engines of the second stage, the payload, and in the case of a space shuttle, also the orbiter. Thus together 16.7 % is available for all engines, the tanks, the payload, and the possible orbiter.

= 0.648, therefore 64.8% of the remaining mass has to be propellant, which is 16.2 %, and 8.7 % remains for the tank and engines of the second stage, the payload, and in the case of a space shuttle, also the orbiter. Thus together 16.7 % is available for all engines, the tanks, the payload, and the possible orbiter.

Applicability

The rocket equation holds true for rocket-like reaction vehicles whenever the effective exhaust velocity is constant; and can be summed or integrated when the effective exhaust velocity varies.

However, it does not apply to other technologies such as gun launches, space elevators, launch loops, tether propulsion and air-breathing engines.

See also

- Delta-v

- Delta-v budget

- Oberth effect applying delta-v in a gravity well increases the final velocity

- Specific impulse

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Mass ratio

- Working mass

- Relativistic rocket

- Reversibility of orbits

References

- ^ К. Э. Циолковский, Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами, 1903. It is available online here in a RARed PDF

- ^ Moore, William; of the Military Academy at Woolwich (1813). A Treatise on the Motion of Rockets. To which is added, An Essay on Naval Gunnery. London: G. and S. Robinson.

- ^ Johnson, W. (1995). "Contents and commentary on William Moore's a treatise on the motion of rockets and an essay on naval gunnery". International Journal of Impact Engineering 16 (3): 499–521. doi:10.1016/0734-743X(94)00052-X. ISSN 0734-743X. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V3K-3Y5FP5P-11/2/c3e98a6cec8f083c93dc4e4e157282bb.